- Home

- Deborah Halber

The Skeleton Crew Page 3

The Skeleton Crew Read online

Page 3

He smiled at a Sofía Vergara look-alike detective behind the desk who, like almost everyone in the building, had a service revolver strapped to one hip. She checked our names on a list and pointed us toward an urn of black coffee, Styrofoam cups, and sticky, cinnamon-scented pastries. I watched Todd mill around, greeting people he recognized from the crime conference circuit.

I thought Todd’s aquiline nose, thick chevron mustache, ragged soul patch, chestnut-brown eyes, and white teeth made him good-looking in an early-’80s sort of way. Around five-seven, his shaggy dark brown mane gained him a couple of inches. He exuded a Zen-like calm—until he started to speak. His middle Tennessee dialect—Tommy Lee Jones with a dash of Jed Clampett—was so rapid-fire, I had trouble recognizing it as English. “Dead” became “day-ud,” “well” was “way-eel.”

Besides losing the flip-flops and baseball cap I would come to recognize as integral parts of his look, Todd hadn’t dressed for the part of speaker. In a short-sleeved golf shirt and jeans, he angled down the microphone; the previous presenter was a head taller. “I wore a suit in Vegas and everyone thought I was Tony Orlando,” he told a sea of unsmiling cops. “I don’t wear a mic because it wears down the chest hair.”

After twenty minutes of leading the audience through the various ins and outs of using an online database to compare the details of the missing and the unidentified, Todd relinquished the podium to a forensic pathologist whose PowerPoint was a parade of gore: a corpse’s face and neck striped from sternum to forehead with perfectly even, vertical tire treads; skulls bashed in by hammers or riddled with bullet holes; severed limbs, bloodied and mangled or denuded of skin. No one in the audience blinked.

Maybe Todd logged a couple of converts among law enforcement that day. He knew what he was up against. He’d spent years during his one-man investigation of Tent Girl trying to gain the confidence of cops who didn’t hide the fact that they considered him a time-sucking, death-obsessed wacko. He’d lost track of the number of times he’d been turned away, ridiculed, dismissed, hung up on.

No one was actively investigating Tent Girl back then, almost no one was keeping track of the thousands of other unidentified bodies, and no one was effectively trying to match them to the tens of thousands of people still listed as missing. Incredibly, it would take thirty years from the time the issue was first raised for a universally accessible system dedicated to this purpose to materialize. One of the first people to advocate for such a thing was a dumpling-shaped woman in wire-rimmed spectacles who took the stage shortly after Todd: Dr. Marcella Fierro. Fierro started her career as an ambitious young medical student in upstate New York. Only the ninth woman in the country certified in forensic pathology, Fierro joined Richmond’s Medical College of Virginia Hospitals and the office of the Virginia medical examiner, where she would one day meet author Patricia Cornwell. As a technical writer for the medical examiner in Richmond, Cornwell gained intimate knowledge of forensic science—material that would later surface in her wildly popular crime novels. And Fierro became the model for Kay Scarpetta, the unassailable expert pathologist featured in more than a dozen of Cornwell’s best-selling books. (Fierro points out that she is not the physical model for Scarpetta: “Kay is blond, blue-eyed, and a hundred and fifteen pounds. I’ve never been blond, I have brown eyes, and I haven’t weighed a hundred and fifteen pounds since I was twelve.”)

In the 1970s, more than a decade before her friendship with Cornwell began and when Todd Matthews was still in kindergarten, Fierro heard a speaker at an American Academy of Forensic Sciences meeting call for a national registry for the unidentified. The subject resonated with her. Fierro had noticed that if a nameless but potentially recognizable body—an unidentified, or UID in law enforcement lingo—turned up on her autopsy table, the police took photos and issued a missing-person report or an APB. But if the body had decomposed or lacked fingerprints, “forget it,” Fierro said. “There was really nothing.”

It was obvious—to Fierro, at least—that this was a problem. It turned out to be a bigger problem than she could have imagined, involving law enforcement agencies, police departments, coroners, and medical examiners across fifty states with overlapping responsibilities for the unidentified and a communication breakdown that rivaled that of Apollo missions on the far side of the moon.

Big urban police departments considered their smaller, more rural counterparts hicks and rubes; professionally trained medical examiners with advanced degrees looked down on locally elected coroners. Consequently, if a missing person became an unidentified body several states away, or even in the next county, the case might remain unsolved because public service officials in one location didn’t deign to share information or confer with their counterparts elsewhere.

They did all agree on one thing: no one wanted to talk to the public.

Theories abound on why law enforcement entities are so fiercely autonomous. Major urban police forces as we know them have been around since the mid- to late nineteenth century, state police forces evolved independently at the end of the nineteenth century, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation came into existence even later. Within a single municipality, police power can be divided among dozens of separate organizations, creating legions of fiefdoms. It was unclear whether a stray human body “belonged” to the medical examiner or to law enforcement. The fact was, no one entity owned the problem of UIDs, and early on, no one seemed to know how to go about identifying them.

Yet seeds were being sown. Around the time that Fierro was performing her first autopsies in Richmond in the mid-1970s, a police artist and an anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution joined forces to attempt to elicit the “personality” of a skeleton found in woods adjacent to a Maryland industrial park. Science had not yet enabled investigators to reconstruct personality based solely upon the fragmentary remains of an individual, the pair wrote. But they decided to try to give one victim a presence that others might recognize.

The anthropologist determined that the victim was a seventeen- to twenty-two-year-old female, shorter than average, with a skewed right hip and a once-broken collarbone. Digging through evidence boxes, the police artist pulled out jewelry and a sweater found with the remains. He fingered strands of her long hair, traced and measured the skull, and started to sketch, conferring with the anthropologist on the shape and placement of her eyes, ears, and mouth.

Within days of the finished sketch’s appearing in a local newspaper, police had identified Roseanne Michele Sturtz, who had not been seen since the previous year. People who knew her said that the twenty-year-old nightclub dancer favored one leg and had broken her collarbone when she was six.

A few years later, a father devastated by his son’s brutal murder funneled his considerable energy and intensity into shaking up what he perceived as a deeply flawed system. After the disappearance and horrific 1981 murder of six-year-old Adam, Florida hotel developer John Walsh became an impassioned advocate for the missing. He joined forces in 1984 with the then-new nonprofit National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (its acronym, NCMEC, is pronounced “nick-mick”) in Alexandria, Virginia, which Congress would later sanction as the official national resource center and information clearinghouse for missing and exploited children. Walsh went on to host America’s Most Wanted, among the first TV shows to enlist the public’s help in solving crimes, paving the way for a growing movement: ordinary citizens working on cold cases. A decade later, the web sleuth phenomenon would force law enforcement’s hand in ways Walsh likely never anticipated.

Fierro continued to forge her own connections within forensics and with the unidentified. When she had treated living patients, asking probing questions always gave her insight into what might be ailing them. So when confronted with UIDs—whom she saw as patients who happened to be dead—she talked to them as well. She asked them to tell her their stories, and she found that when she examined them the right way, they responded

as eloquently as if they could speak, telling her whether they were right- or left-handed, if they had ever been seriously injured or undergone surgery, their age and race, whether they took care of their teeth, if they had ever borne a child. No detail was insignificant. “You have a genius for minutiae,” Watson once chided Sherlock Holmes, who routinely made mental notes of esoteric facts. Holmes countered that recognizing distinctive calluses and scars on the hands of cork cutters, weavers, diamond polishers, and other tradesmen might help him identify an unclaimed body.

In the late 1980s, Fierro wrote a handbook for pathologists on tricks of the trade for conducting postmortem examinations of unidentified remains. She approached FBI officials, who, years after the American Academy of Forensic Sciences speaker had called for a registry of the unidentified, were still not the least bit interested in setting up such a thing. Considering that the FBI wouldn’t have a working computer system that allowed its thirteen thousand agents to track case files electronically for almost another three decades, she shouldn’t have been surprised.

Around the time Fierro was learning the silent language of the unidentified, Todd Matthews was a twenty-year-old factory worker in Livingston, Tennessee, who possessed an odd sense of kinship with the deceased. The fact that there were many like Tent Girl, nameless and forgotten, wouldn’t reach the public consciousness for more than another decade. The way one longtime forensic anthropologist saw it, when Todd managed to identify Tent Girl, he triggered a gold rush. The case details of long-forgotten UIDs started to find their way out of dusty filing cabinets and onto websites, becoming an untapped mother lode of potentially useful crowdsourcing data.

CSI, with its gee-whiz forensics, premiered in 2000. The following year, 9/11 struck, and the desperate need to identify thousands of victims of the World Trade Center attacks helped advance DNA as a forensic tool. Some of the pieces for a new approach to UIDs had started to fall into place.

* * *

At the Virginia Beach conference, I met Betty Dalton Brown, an amateur sleuth living in North Carolina who spoke to Todd Matthews almost daily but had never met him in person. “I think he’s around sixty, very distinguished, gray hair, goes to the opera,” she said. “He’s the one with the mullet,” a Pennsylvania man informed her. (Todd insisted later that he was going for long-haired country boy, not a mullet.)

I recognized Betty as one of the scheduled speakers who, just before the conference, had grimly taken in the sea of seats in the empty auditorium and muttered, “Anybody have any Scotch?” Betty, petite, with shoulder-length dirty-blond hair, looked tough and feminine that day in black Western boots, black jeans, and a frilly checked blouse. Despite her attack of nerves, she pulled off her first-ever public talk about her search for a missing half brother, and I learned later that Betty has an uncanny knack for finding almost anything and anyone on the Internet. She’d blow away in a strong wind and she can be prickly, to put it mildly, but I decided that, in a showdown, I’d want Betty Brown on my side.

After the official program in Virginia Beach ended, a small group that included Betty, Todd, and me reconvened in a Holiday Inn lounge. I gazed at Todd’s Hawaiian shirt, baseball cap, flip-flops, and ebullient hair. Knowing Todd only a matter of hours, I was a little worried that any minute he was going to confess that he believed the unidentified dead had been abducted by aliens or would be resurrected as vampires, and then I was going to have to stop myself from saying what I was thinking, which was something along the lines of What a weirdo hillbilly fanatic. I didn’t tell him it wasn’t considered normal in most circles to keep human skulls in your basement, as he mentioned he did, or to wear a soul patch.

I didn’t have to say those things. Todd seemed resigned to the disdain with which some Yankees viewed him, and viewed the South as a setting for surreal fantasies and historical romances, Disney movies, and gothic nightmares of descents into madness. Hans Christian Andersen meets William Faulkner.

Sitting over blue drinks that night with the web sleuths and a jovial forensic expert from a Texas university, listening to stories laced with details of decomposition as we ate rare burgers, I was wondering what kind of hideously ghoulish subculture I had gotten myself mixed up with. But as the night wore on, the waves crashed along the far side of the Virginia Beach boardwalk, the gory anecdotes became funnier, the blue drinks kept coming, and my companions were turning out to be excellent company.

* * *

In the wake of Todd Matthews’s successful identification of Tent Girl in 1998, many civilian sleuths took to the Internet to search out potential matches between the unidentified and the missing. By 2001, the same unidentified corpses that were once almost universally ignored had evolved into tantalizing clues in a massive, global version of Concentration played around the clock by a hodgepodge of self-styled amateur sleuths, a dedicated skeleton crew that shared a desire to match faces to names—and names to dead bodies. Anybody with an idealistic bent, a lot of time, and a strong stomach could sign on: a stay-at-home mom in New York, a chain store cashier in Mississippi, a nurse in Nebraska, a retired cop and his exotic-dancer girlfriend in Houston.

Venturing into the web sleuths’ demimonde of aliases and screen names and pseudonyms, I came across SheWhoMustNotBeNamed and Yoda and abcman and Texaskowgirl. They were an underground society whose members wouldn’t recognize one another if they passed on the street; their real-world personas were unknown to the kindred souls they encountered online.

On Websleuths Crime Sleuthing Community, users commented on celebrity fiascos such as Lindsay Lohan’s latest woes, reports of serial pedophiles, Oscar Pistorius’s arrest in the shooting death of Reeva Steenkamp. Among the many topics being tossed around at any given moment was the unidentified. The last time I checked, Websleuths contained almost 85,000 separate posts in more than 3,500 topic threads dedicated to the unidentified. Far fewer, admittedly, than the one-million-plus posts about Caylee Anthony, but at least some of those who spent their time in the realm of the unidentified were actively trying to match faces with names rather than simply rubbernecking at human train wrecks. When new users described how they found their way to the forum, their words made them seem benevolent, socially conscious—and a tad fanatical.

I’ve been fascinated with true crime stories for years . . . If I ever find a match [for] just one [unidentified corpse], I’ll know I made a difference in the world.

—FLMom

i have been surfing cold cases on the internet for a few years now . . . it started when i read about a jane doe in upstate new york. I couldn’t believe that one so young was still not identified after all that time—on one site i saw the photos from the morgue and they just burned in my brain—i keep checking sites for young girls missing from the 1970s to see if i can find a match—nothing yet. but her case haunts me.

—Jeanne

Then there’s Paul, who works for a medical examiner and wants to provide identities to the “many unfortunate subjects who have as yet no name.” Scott, another budding addict, wrote a paper for a college English class about Princess Doe, an unidentified young girl found in 1982 at Cedar Ridge Cemetery in Blairstown, New Jersey, and kept coming back to the websites. I’d always thought of the dead, as, well, dead, yet I had come across a community that embraced deceased strangers like long-lost loved ones who happened to be more likely to get in touch via Ouija board than cell phone.

By solving Tent Girl, Todd Matthews had unwittingly tapped into a like-minded posse who began to call, text, or e-mail one another almost daily, across time zones and often late at night when their families were asleep. They compared notes on cases, dug through archives, posted on true-crime forums and online bulletin boards. Websleuths.com, Can You Identify Me?, the Charley Project, JusticeQuest, and Porchlight International for the Missing and Unidentified joined the earlier sites such as the Doe Network and the Missing Persons Cold Case Network. They forged a growing commonality while keeping

a low profile among the uninitiated, because it’s hard to work human remains into cocktail conversation.

Over the years, as the posse grew, outside his trusted inner circle Todd found himself negotiating a minefield of politics, not always successfully. Unleashing the web sleuths, Todd had created a monster: an army of gung-ho volunteers demanding sensitive information from police and clamoring to pass along their proposed solutions. Police investigators dismissed the early amateur sleuths as busybodies, hung up on them, refused their calls, ignored their messages, and generally disparaged the people they called the Doe Nuts.

At first, it seemed to me that the cause attracted a stalwart band of do-gooders, impervious to the gruesome nature of the work like macabre Robin Hoods. I was unaware back then that this subculture was no more immune from backstabbing and vindictiveness than Wall Street. In the web sleuth world, achievement could be measured by posting the most information, say, or by attracting hundreds of members, but everyone agreed that matching a missing person with unidentified remains was the Holy Grail. In pursuit of the grail, web sleuths of vastly different backgrounds, worldviews, and political leanings, drawn to the quest for highly personal reasons, found themselves camped out in a corner of cyberspace with individuals they would likely never have otherwise met or chosen to bunk with.

Strung up like dirty laundry was evidence of their clashes: forum members banned for perceived or real infractions, users vilifying one another via fake online identities.

Faceless, behind screen names, separated by time and space, web sleuths baited their perceived enemies with insinuations and wisecracks. Some were capable of elevating philosophical rifts and personality clashes into out-and-out turf wars. “Websleuths is SUPPOSED to be [a] TRUE CRIME forum,” posted someone who variously called herself JaneInOz and Pepper. “However there are now so many rules about what can and can’t be said, that no meaningful discussion can take place without someone taking offense . . . Every discussion seems to turn into a bash fest.” I felt JaneInOz hit the problem squarely on the head when, at the end of a diatribe directed at Utah-based Websleuths.com co-owner Tricia Griffith, she concluded, seemingly without a trace of irony, “I don’t dislike you. Heck, I don’t even really know you.”

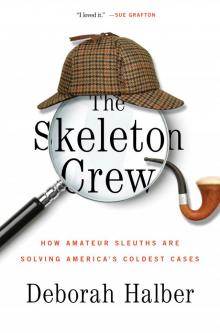

The Skeleton Crew

The Skeleton Crew